On October 17, 1859, a night watchman for the U.S. Armory shows up ten minutes late to his midnight shift, but he can tell immediately that something is wrong. Less than sixty hours later, approximately fifteen people are dead, with several others wounded. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War (2011) examines John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and how it transforms abolitionist sentiment into direct action, turning the tide for both the North and the South over the question of slavery.

Midnight Rising begins with the years leading up to Brown’s radical plan to capture a federal armory in the South and incite a rebellion among enslaved people. The son of a Calvinist preacher who actively participates in the Underground Railroad, Brown grows up in an anti-slavery environment. As he matures, his abolitionist convictions deepen. In the post-9/11 world, many label Brown a terrorist, but Horwitz offers a more nuanced interpretation:

“Viewed through the lens of 9/11, Harpers Ferry seems an al-Qaeda prequel: a long-bearded fundamentalist, consumed by hatred of the U.S. government, launches nineteen men in a suicidal strike on a symbol of American power. A shocked nation plunges into war. We are still grappling with the consequences.

“But John Brown wasn’t a charismatic foreigner crusading from half a world away. He descended from Puritan and Revolutionary soldiers and believed he was fulfilling their struggle for freedom. Nor was he an alienated loner in the mold of recent homegrown terrorists such as Ted Kaczynski and Timothy McVeigh. Brown plotted while raising an enormous family; he also drew support from leading thinkers and activists of his day, including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Henry David Thoreau. The covert group that funneled him money and guns, the so-called Secret Six, was composed of northern magnates and prominent Harvard men, two of them ministers.

“Those who followed Brown into battle represented a cross section of mid-nineteenth-century America.”

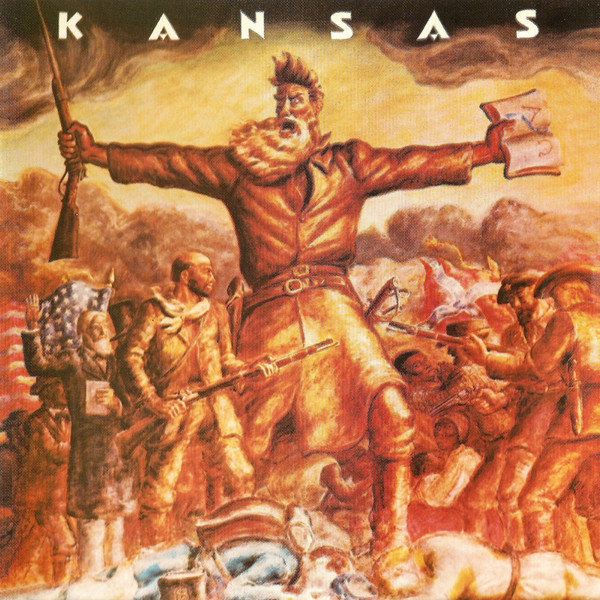

With the implementation of the Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854), which allows settlers in new territories to determine by popular vote whether to permit slavery, tensions between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions escalate. Each side seeks to influence whether Kansas will enter the Union as a free or slave state. Early violence aimed at driving out “free staters” before the vote enrages Brown. He heads to Kansas to give pro-slavery settlers a reason to fear in return.

“Brown didn’t wait long to take up arms in the battle he’d come to join. A few weeks before his arrival, the territory’s proslavery legislature—‘elected’ amid rampant fraud—put into force some of the most extreme laws in antebellum America…”

Brown’s actions are bold and bloody. Horwitz recounts the Pottawatomie Massacre, in which Brown and a handful of his sons and followers brutally execute five men with broadswords in retaliation for recent pro-slavery actions—the caning of free-state senator Charles Sumner on the Senate floor and the sack of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces.

Months later, Brown becomes a household name across the country as he and his band of thirty men battle 250 pro-slavery attackers. Newspapers dub him “Osawatomie Brown,” either celebrating or condemning his personal crusade against slavery.

The book slows in pace as Brown embarks on a public speaking and private fundraising campaign against slavery. He gathers investors and weapons, bringing him into contact with figures like Harriet Tubman, Henry David Thoreau, Frederick Douglass, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

According to Horwitz, Brown struggles to recruit fighters for his next mission. Many are deterred by his vague plans, and his dwindling funds fail to inspire commitment.

Once Brown moves his small force of eighteen men to Maryland to stage their attack, the narrative regains momentum. The raiding party captures sixty hostages, including Colonel Lewis Washington, great grandnephew of George Washington, and John Allstadt, a prominent landholder and slave owner.

After the initial firefight between the townspeople and Brown’s men, President Buchanan dispatches future Confederate leaders Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart to restore order and end the standoff. When Brown refuses to surrender, Lee’s troops launch a swift, three-minute assault that brings the raid to an end.

Horwitz drives his main point home in the final chapters as Brown and the few surviving raiders are tried and executed by the State of Virginia. Prior to the raid at Harpers Ferry, most Northerners speak only in general terms about ending slavery. Afterward, Northern public opinion hardens, demanding federal action. Southerners respond in kind, leading swiftly to secession.

The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

Tony Horwitz also authored two other works exploring the legacy and memory of the Civil War. His book Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (1998) focuses on how the modern South remembers and mythologizes the Civil War. His final book, Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide (2019), looks back at the divisions that Frederick Law Olmsted observes in the South in the 1850s and compares them to those of today.

Leave a comment